Will the Berlusconi Sentence Stick?

October 29th, 2012

October 29th, 2012

Cross-posted from Transparency International’s Space for Transparency blog.

Silvio Berlusconi, the former prime minister of Italy was sentenced on 26 October to 4 years in prison for fraud but because of Italy’s laws limiting the length of trials, he is unlikely to serve any time.

Silvio Berlusconi, the former prime minister of Italy was sentenced on 26 October to 4 years in prison for fraud but because of Italy’s laws limiting the length of trials, he is unlikely to serve any time.

Headlines around the world read “Berlusconi gets four year jail sentence.” But Berlusconi is unlikely to see the inside of a cell following his conviction for fraud, not because an appeal will overturn the case but because the case will be closed under Italy’s short statute of limitation laws.

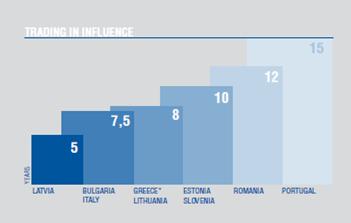

How trial limits vary across Europe. Prosecutions for abuse of public function and bribery in Italy must end 7.5 years after the crime last happened. For money laundering, cases can last 15 years. Click the picture for the full report (p. 26).

Under Italian law Berlusconi can appeal to two more courts, a process that is likely to take several years, and as the Financial Times is already reporting, Italy’s strict limits on the length of trials – the “statute of limitations” – means the charges will very probably evaporate at the end of 2013 or early 2014.

If the courts are serious about their convictions, they need to find a way to make the punishments stick. Italy has one of the least effective statutes of limitations in Europe. Portuguese prosecutors get three times as long to finish a bribery case (22.5 years) than their Italian colleagues (7.5 years). The Council of Europe have long called for reform.

A report we issued in 2010 warned that the system “constitutes a significant reason for impunity.”

Or, as the Financial Times reports:

It is not the first time that Mr Berlusconi has received a jail sentence, but on three previous occasions he has always successfully appealed or had convictions timed out, or in other cases driven through a change in the law to defeat prosecutors.”

Will it be different this time?

Our research suggests not.

Exceptionally high numbers of cases are being dismissed in Italy: from 2005-2009, 10 to 13 per cent of all criminal court proceedings have been closed because they ran out of time, meaning that one in 10 trials ended with impunity for the alleged offender. That is more than 150 000 cases a year. In Hungary, the rate was less than one per cent. In Finland, it was less than 0.1 per cent.

Our report noted why this makes it especially hard to tackle corruption:

Problems arise due to the hidden nature of corruption: when the offence is discovered, a considerable period of time has often elapsed and the remaining time is often not sufficient to complete the proceeding.”

This is exactly what is happening this time around.

It is not fair for Italians to see those in power held to account and then slip off the hook because of a technicality. It breeds cynicism and contempt for the justice system and gives the impression that those in power can act with impunity. Everyone should have the right to appeal, just allow the courts the time to hear the cases rather than throw them out.

There are several ways to solve this

First, the statute of limitations should be revised to suit the nature of the crime. Corruption cases can take a long time to prosecute. The Minister of Justice Paola Severino said she is planning to draft a specific law for statutes of limitation.

In the meantime, Italy is discussing a new anti-corruption law. The latest draft does not mention statutes of limitations specifically, but changes in the penalties for corruption could make a difference. The length of time a case can be heard in the courts depends very much on the maximum penalty for the crime.

If corruption and fraud cases are given the stiff sentences they deserve, the prosecutors will have more time to prove their cases.