Lawmakers take first step to revealing anonymous companies in the US

June 28th, 2017

June 28th, 2017

Today, a bi-partisan group of lawmakers introduced legislation that would begin to lift the veil that currently shrouds company ownership in the United States. And this is good news, because the US has a long way to go if it’s to join those leading the way on financial transparency.

Despite belonging to numerous international organizations aimed at cutting down on illicit finance, taking a tough line on terrorist financing, and actively prosecuting financial crimes in the courts, many US states remain some of the easiest places in the world to open a company without having to disclose the beneficial owner–the real, ultimate person in control or benefiting from the company. This odd dichotomy of rhetoric versus reality has enabled US corporations to be used in everything from drug trafficking and arms deals to Medicare fraud and tax evasion.

But today’s announcement of the Corporate Transparency Act, introduced by Reps. Peter King (R-NY-2), Carolyn Maloney (D-NY-12), Ed Royce (R-CA-39) and Maxine Waters (D-CA-43), would make it more difficult for US companies to be used to commit a crime. The legislation would require the Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) to collect information on the beneficial owner(s) of companies incorporated in the US, if this isn’t already happening at the state level. And a bi-partisan group of Senators have introduced the True Incorporation Transparency for Law Enforcement (TITLE) Act, a similar piece of legislation, which would instead have states collect the information. The Senate bill was introduced by Senators Charles Grassley (R-IA), Dianne Feinstein (D-CA) and Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI).

It’s important for US lawmakers to wake up to the fact that the US is a safe haven for an increasing amount of the world’s dirty money, whether it be embezzled from state coffers halfway across the world or siphoned from a Medicare fraud scheme right here in the US. And with places like the European Union committed to bringing transparency to company ownership, the US has become an even more attractive destination to hide one’s money.

While examples are rife, a recent investigation by The New York Times showed that a majority of new high-end real estate in Manhattan was being purchased via companies in which the true owner was obscured. For corrupt politicians or those looking to move dirty money, purchasing a $10 million condo with a company that’s untraceable can be more reassuring than hiding the funds in a bank account. After all, bank accounts can be frozen, as some sort of paper trail may eventually be uncovered. But a condo with hidden ownership, that’s a far safer investment in a criminal’s eyes.

The Times investigation, and a sustained push by civil society organizations, prompted US Treasury’s FinCEN to begin a pilot program to look into suspicious real estate purchases. The pilot program required buyers of high-end real estate in certain cities to disclose the true owner when a company was used to make the purchase. The program returned a lot of question marks: more than a quarter of the purchases examined were deemed to be ‘suspicious’ in nature. This prompted FinCEN to expand the program.

But it’s not just real estate that’s at risk with anonymous companies.

Lax corporate transparency in the United States has harmed citizens of countries on the other side of the globe. FTC member Global Witness has compiled a number of cases where US companies were used to commit crimes in other countries, and some of the results are staggering. Whether it was a Moldovan gang using shell companies in Kansas and Ohio or the Iranian government using an anonymous company in New York to own a Manhattan skyscraper, thus bypassing sanctions, there’s one prevailing theme: US companies are far too easy of a conduit for criminality.

The lack of uniform, simple disclosure requirements have become a booming business for a handful of US states that have welcomed the secrecy. Mossack Fonseca, the firm made famous by the Panama Papers for offering a dizzying array of corporate secrecy options, even had an affiliate branch in Nevada, a state known for lax disclosure. Delaware, which was recently ranked in an academic study as the second easiest place in the world to open an anonymous company, receives almost a quarter of its state budget from company incorporation fees. It was a favorite of Viktor Bout, the Russian arms dealer, who set up a slew of companies based in the state.

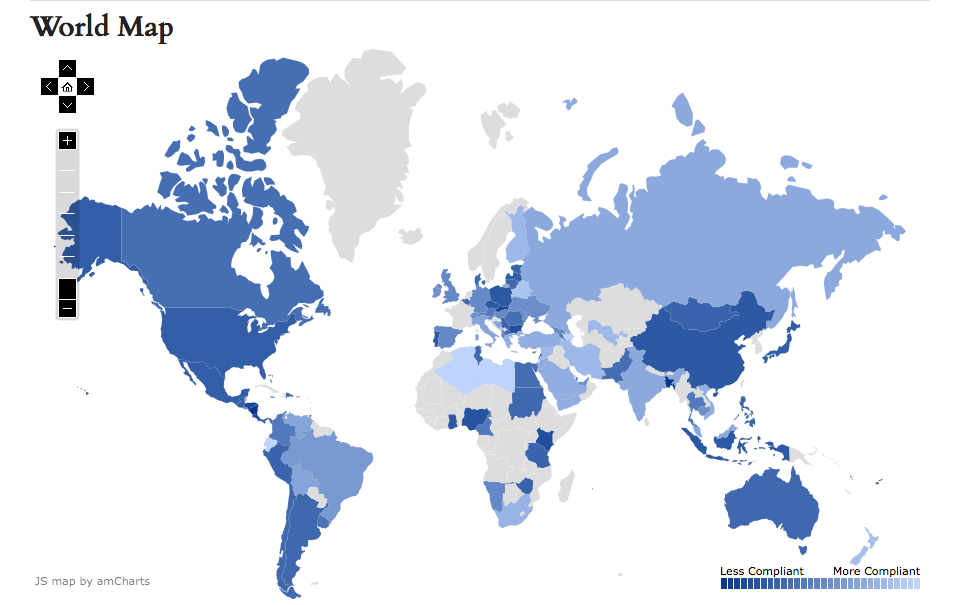

But an uncomfortable fact remains: the US has a long way to go to catch up to the leaders of the financial transparency movement.

A number of countries around the globe already collect information on beneficial owners, and a growing number are calling for this information to be made public in central registers. The UK and Ukraine have set up public registers of beneficial ownership information, and the EU is currently debating not if their member states’ registers should be public, but to what extent they should be made available. Countries outside of Europe, from Ghana to Afghanistan, have committed to public registers, as well.

As the chorus for public registers has grown louder, more people are recognizing that simply collecting the information ultimately may not be enough. It’s vital that journalists, civil society advocates, and those from other countries are able to analyze ownership data. As companies can be used to hide your tracks halfway across the world, keeping this information only in the hands of law enforcement could stifle independent investigations by journalists and researchers.

While the US will have to eventually consider public registers if it truly wishes to shed its secrecy jurisdiction status, finally beginning to ask the question of ‘who owns it’ is certainly a laudable start.