Five Key Takeaways from UN FACTI Panel Release

March 11th, 2021

March 11th, 2021

Last week, the United Nations High-Level Panel on Financial Transparency, Accountability, and Integrity (FACTI) Panel released its much-anticipated findings. The momentous release, as FTC wrote in response, “established a new global standard on financial transparency.”

As FTC member Latindadd wrote, the report is “an important piece of work for a generation of proposals for structural reforms in the global financial system.” Or as FTC member Tax Justice Network wrote, it was a “tide-turning moment in the global struggle for tax justice.” The FTC actually organized a high-level event the day after the UN FACTI Panel’s report, discussing its implications and impact, which can be watched here:

But what did the FACTI Panel report actually find, and why was its final report so widely praised for its findings? Here are five key takeaways from the FACTI Panel’s release that highlight the report’s importance — and why the FACTI Panel can help turn the tide against illicit finance.

For years, getting a handle on the actual financial impact of illicit financial flows — things like trade manipulation, organized crime, and corrupt payments to public officials — and tax injustice has proven difficult, not least because so many of those financial flows rely on financial secrecy and financial anonymity. However, the UN’s FACTI Panel report highlighted the following range of estimates, many of which are staggering. Among the FACTI Panel’s findings:

For further discussion of these top-line findings, be sure to watch the UN FACTI Panel’s launch event:

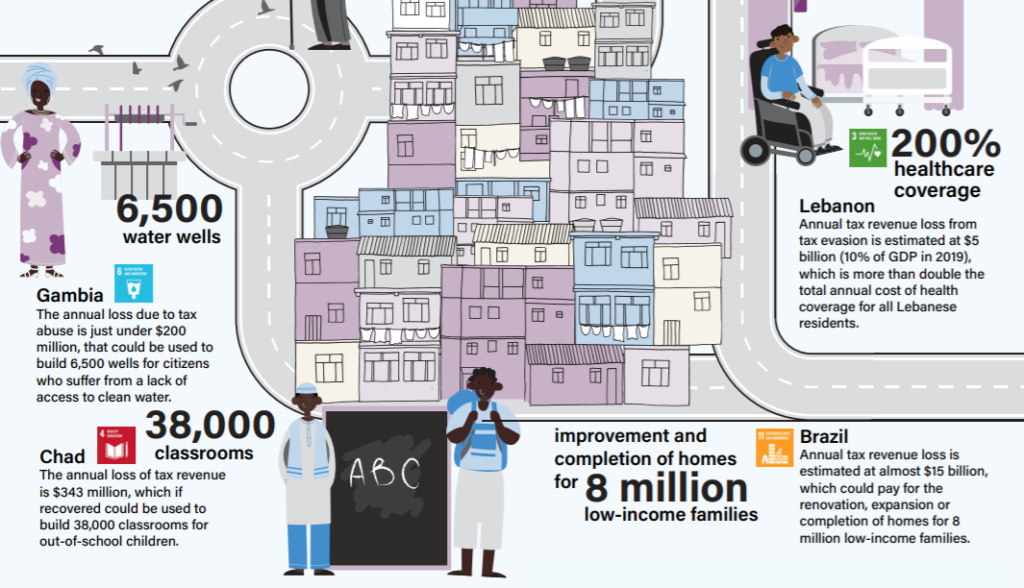

While the numbers in the FACTI Panel report offer clear insight into the magnitude of the problem of illicit financial flows, numbers as massive as billions or trillions can sometimes be difficult to wrap our heads around. Fortunately, the FACTI Panel helps quantify what exactly those numbers mean — and what they would mean for the countries and populations watching their wealth disappear into the world of offshoring, financial secrecy, and tax havens. Among the examples:

Source: FACTI Panel

Among the policies proposed by the FACTI Panel, perhaps none stood out more than the call to create a United Nations Tax Convention. As the report, which offered a total of 14 high-level recommendations, noted, “international tax norms, particularly tax-transparency standards, should be established through an open and inclusive legal instrument with universal participation,” and should be done via a UN Tax Convention. Such a convention could create fair, impartial mechanisms for resolving international tax disputes, or provide for mechanisms of taxing multinational corporations.

As FTC wrote in response to the call for a UN Tax Convention:

The FTC particularly applauds FACTI’s calls to set up a UN Tax Convention, so that creating global tax standards is no longer led by bodies such as OECD, FATF and G20, which primarily represent the interests of countries in the global North and weakly aligned with human rights and sustainable development goals. This move would open the way for countries in the global South – including those most affected by the $500-$600 billion in revenue losses every year from profit-shifting by multinational companies – to finally have a say on how global finance is governed for the benefit of everyone, especially those most impacted by its harmful and abusive aspects.

.@donalddeya: "Yesterday was a very profound day. The @FACTIpanel report was quite profound—they went further than we thought… I consider yesterday to be as momentous a moment" as the UN founding, "and the beginning of a new campaign of economic emancipation."#FTCtalksFACTI

— Financial Transparency Coalition (@FinTrCo) February 26, 2021

Much of the FACTI Panel report centered on one specific “sub-type” of illicit financial flows: “corporate profit-shifting, or the shopping around for tax-free jurisdictions by multinational corporation,” costing jurisdictions somewhere between $500 and $650 billion per year. The UN FACTI Panel, however, offered a clear solution: a global minimum corporate tax. Such a proposal would create a taxation “floor,” or a minimum at which every corporation would be taxed. Corporations would still be free to look for other jurisdictions to register things like profits, but a global minimum corporate tax would ensure that the entity “would be subject to tax on its global income at the minimum rate regardless of where it was headquartered,” as the UN FACTI Panel wrote.

While the creation of a global minimum corporate tax would, on its own, reduce harmful tax competition, the UN FACTI Panel went one step further. The UN FACTI Panel offered a proposed range for the new global minimum: 20%-30% on corporate profits. Not only does the estimate place a significant “floor” for global corporate taxation, but it also offers a range of flexibility for jurisdictions looking to incentivize sustainable development investment.

While much of the FACTI Panel’s report dealt with the dollars and cents behind illicit financial flows — tax rates, fiscal losses, and the trillions laundered every year — one of the UN FACTI Panel report’s most impactful sections centered not on the funds themselves, but on those who set up the offshoring and tax haven systems in the first place. These so-called “enablers,” including accountants and lawyers, are the professionals who hold the keys to the financial sector, and who often escape scrutiny and regulatory oversight.

For the UN FACTI Panel, however, the time has come to hold these “enablers” accountable. Governments, as the report found, “should develop and agree [on] global standards/guidelines for financial, legal, accounting and other relevant professionals.” As the report continued:

Professionals such as bankers, lawyers and accountants are important players in international business dealings. As advisors, facilitators, negotiators and mediators, they are right to look after the interests of their clients. However, this does not excuse them from acting anything less than ethically and in line with global values, norms and standards.

While there is a widespread practice of criminal prosecution of those complicit in aiding or abetting violent criminal offences, there is no corresponding practice for financial crimes. This is puzzling because some enablers of illicit financial flows make the planning and execution of financial abuses and crimes their unique selling proposition to their clients.

As the report concluded, “self-regulation does not work.” And as FTC member Eurodad wrote, “The UN FACTI report must be a starting gun for international action to stop illicit financial flows, what is needed now is for our governments to get to work.”