Crackdown on tax havens, for some

December 7th, 2016

December 7th, 2016

There’s an in-depth piece published today in the Financial Times that examines the upcoming implementation of the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard (CRS) for the automatic exchange of financial information. This new standard would allow countries to share information regularly on each other’s citizens who may be hiding money illegally abroad. For example, France will provide Germany with information on German citizens who have money in French banks, and in return, France will receive information on its citizens stashing money in Germany.

Since its inception, the exchange has has been billed as a blow to tax havens around the world, and to banking secrecy and illicit financial flows as a whole. And in many respects, the exchange system seems to have had impacts, even before it has become operational.

From the FT (paywall):

The goal should be to make the Bahamas “the Monaco of the Caribbean”, says Ryan Pinder, former minister of financial services on the islands. He told MPs in the summer that offering tax residency to wealthy people would create a lifeline for the Bahamian economy at a time when the global crackdown on evasion was eroding its conventional offshore business.

But time is running out for investors wanting to dodge a transparency drive designed to squeeze tax evaders out of existence. By the end of the year countries from Albania to Vanuatu will have instructed financial services companies to begin collecting details of bank balances, interest, dividends and income from insurance products earned by clients living overseas.

The data will start criss-crossing the world from September, eventually ending up at the tax authority of the investor’s home country — potentially triggering investigations.

This global move is forcing a decisive break with the longstanding commitment of dozens of tax havens to protect the privacy of their clients. The islands, small states and principalities that built their prosperity on secrecy have all been forced to open up.

Previously, in many instances, a government would have to submit a specific request each time it wanted information from another jurisdiction, which was costly and time consuming. But the CRS will prompt the automatic transfer of financial information, greatly reducing the number of hoops a tax administration must jump through in order to receive information. And many secrecy jurisdictions have signed up to the new system, including old havens like Switzerland, and some less thought of ones, like Vanuatu and the Seychelles.

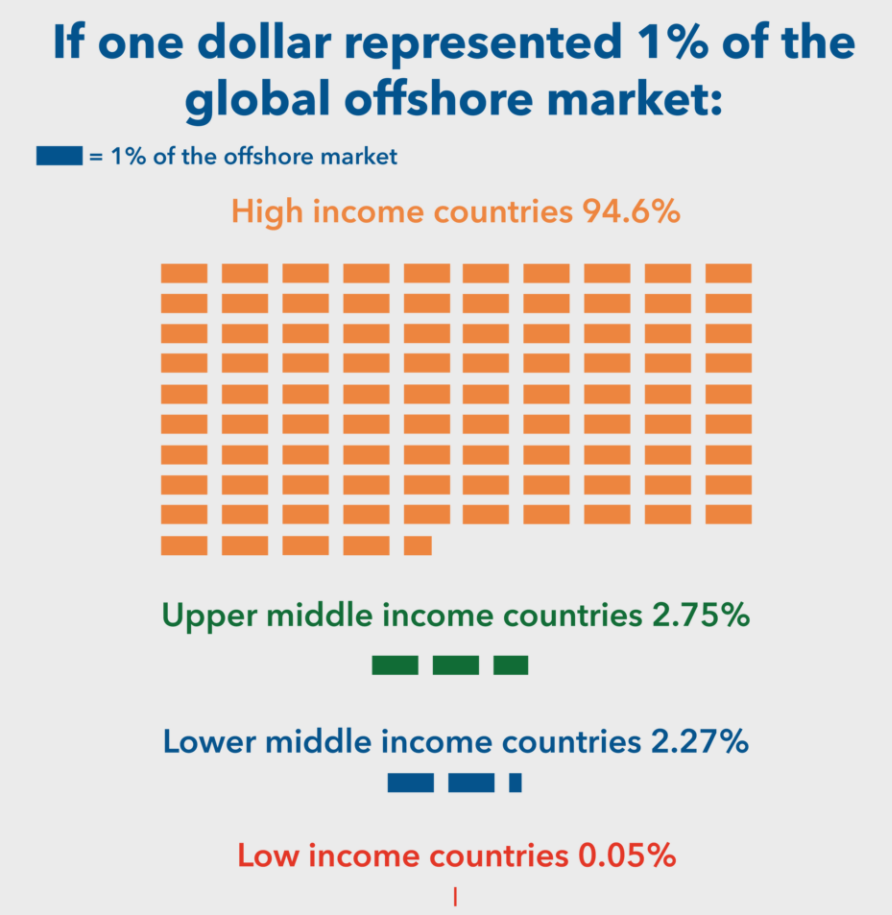

But there is a glaring caveat, which gained little footprint in the FT’s article: many low income countries, who often suffer disproportionately from tax evasion and illicit financial flows, won’t be able to take part in the system, at least not any time soon. While the intent behind the G20/OECD information exchange is laudable, there are a number of requirements that many low income countries simply won’t be able to meet from the start, making it difficult for them to participate.

The biggest of these hurdles is the ‘reciprocity clause’, which states that to receive information, you must be able to share information about your own financial institutions. This mutual exchange, is of course logical in theory, but in reality making low income countries send information from the start is impractical and unnecessary. While many don’t yet have the manpower or technology to do so, there’s also simply very little money heading into banks in low income countries, but vast sums are flowing the other way. This is why a temporary grace period where developing countries could receive information without sending their own would help, not only to boost the credibility of the CRS, but also the number of members in the exchange. This temporary period of non-reciprocity would provide low income countries with the benefits of tracking money leaving their borders, helping to curb things like tax evasion, while they ramp up their ability to share information of their own.

There’s also another aspect of the CRS that could leave some countries in the dark: simply signing up to the agreement doesn’t automatically mean a jurisdiction will have access to information from all other signatories.

As the FT points out:

The reason is simple: there are likely to be big gaps in the CRS networks, at least initially. While all countries must meet certain standards on data protection, some are choosing to impose extra hurdles that will limit the number of countries that can receive the data.

Switzerland, for example, is selecting exchange partners according to whether they offer taxpayers “sufficient scope for regularisation” — leniency for disclosing undeclared accounts — and are willing to discuss market access for the financial services industry.

Our colleagues at the Tax Justice Network have written in depth on how countries signing up to the CRS have leniency in choosing which countries they exchange information with:

As if this were not complicated enough, the worst obstacle – and main point of this blog – is in the final list of “choices” that countries signing the multilateral agreement (MCAA) have to submit: countries are allowed to choose with whom to exchange information among all other signatories of the MCAA, like in a dating system. This last point is important. It means that the choice to engage in automatic exchanges is at the absolute discretion of each country, even if other countries meet all the legal and confidentiality provisions required by the OECD.

So, it is true, as the FT notes, that the OECD’s automatic exchange system will bring big changes around the globe. But questions remain on what those changes will be and how widespread they will ultimately be felt.